The HALT Solitary Confinement Act Could Save Those From Wrongful Death in NY: The Story of Dante Taylor & His Mother’s Fight for Justice

Dante Taylor committed suicide in October 2017, but it was easily avoidable. Now, the HALT Solitary Confinement Act has been signed into law, and other people like Taylor may be saved from the inhumane and torturous conditions of isolation.

May 2021

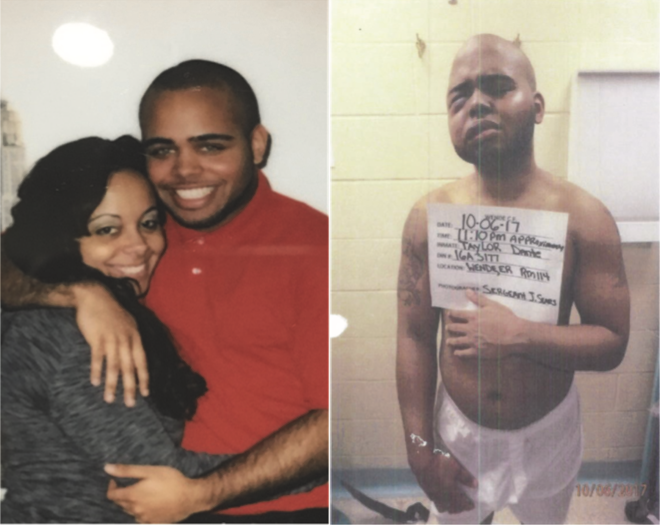

On the night of Oct. 7, 2017 at Wende Correctional Facility in Alden, New York, 22-year-old Dante Taylor took his own life. Taylor was no saint and had already served one year in the New York State Department of Corrections and Community Supervision’s (DOCCS) system. He was a convicted murderer and rapist, and he was also deeply mentally disturbed as he was a victim of abuse as a teen. That night Taylor, according to New York’s own Department of Corrections Medical Board review, was brutally beaten by guards. He had already served four months in Keeplock, a.k.a., solitary confinement, and that, and the systematic torture by officers, eventually was too much for a man who, the guards knew, had a history of attempted suicide.

Taylor’s case was hardly isolated. As of 2019, there were 2,600 people in Segregated Housing Units (SHU), another form of solitary confinement, and 1,000 held in Keeplock. Due to lack of reporting from DOCCS, numbers since 2019 are unknown or probably inaccurate according to reporting by The Correctional Association of New York. But the same report says that more than 30,000 people in New York state prisons are held for more than 15 days, for 22 to 24 hours a day, in solitary confinement.

Solitary confinement of more than 15 days was finally overturned this year, because of high percentages of suicides and lack of sanitary care for those isolated, which were enumerated in the recently passed Humane Alternatives to Long-term (HALT) Solitary Confinement Act, which was signed into law on April 1 by Gov. Andrew Cuomo. According to Assembly member Linda Rosenthal, a HALT Co-sponsor, “30% of all suicides in prison are by people housed in solitary confinement.”

Advocates and lawmakers have fought for the end of inhumane and torturous treatment of people in prison in New York state for over a decade, and the fact that it took this long, says Victor Pate, statewide organizer for the New York Campaign for Alternatives to Isolated Confinement (CAIC), an advocate and survivor of solitary confinement, is a testament to the power of a prison industrial complex and a business model that has profited from torture.

“We've been advocating for the passage of this bill since 2012,” Pate said. He explains that in 2019 there was a chance for the bill to get passed, but it was never brought to the Senate or House floors for a vote. “That only happened as a result of Gov. Cuomo, who had proposed a set of administrative regulations to challenge every confinement reform, which was totally far from what the HALT solitary confinement bill would have done and would have been able to provide, and it just did not go far enough.”

The HALT Act outlines necessary guidelines for those in segregated confinement, including a 15-day minimum solitary confinement sanction, backed by the Nelson Mandela Rules that were adopted by the United Nations in December 2015. These rules state that spending more than 15 days in solitary confinement is torture. The definition of solitary confinement was also updated, describing any cell confinement for more than 17 hours a day as solitary.

Not only does HALT defend people who have spent months, years and even decades in solitary confinement, but also implements alternative rehabilitation options, such as the creation of Residential Rehabilitation Units (RRU) and the elimination of vulnerable incarcerated people being placed in confinement, such as pregnant women, people under the age of 21 or over the age of 55, and those with disabilities.

Darlene McDay, Taylor’s mother, began a fight for justice alongside advocates from the #HALT Campaign after her son’s wrongful and avoidable death, in order to defend and keep those who are still in prison safe from the wrongdoings that her son suffered at the hands of DOCCS.

“People say the system's broken, and then we always say, ‘No, it's not broken. It's exactly how they want it, exactly how they designed it,’” McDay said. “I'm never going to stop,” McDay told the people in prison who tried to defend her son while keeping her in the loop of his experiences behind bars. She told them, “‘Thank you so much for being brave, just always tell the truth. You may not hear anything for a very long time, but don't think that there's ever a moment that I'm going to give up.’”

The Rape and Murder

Taylor grew up in Medford, Long Island with his mother. Throughout his childhood, he suffered abuse from McDay’s former boyfriend, possibly exacerbating the mental anguish he already suffered.

In 2009 at the age of 14 Taylor attempted to commit suicide by hanging himself — this was the first time, but not the last. In his early teenage years, he spent extensive time hospitalized in an in-patient facility for young people with mental health issues. Taylor joined the U.S. Marines four years later, in 2013, shortly after graduating high school. He was still in the service a year later, when he again attempted suicide in April 2014 by hanging for a second time; he was found before he was successful and discharged on medical grounds.

At the age of 19, Taylor, clearly still mentally disturbed, returned home to live with his mother, and still went out to parties and hung out with friends as any person in their early 20s would do. At a party on June 7, 2014, court records would later show, Taylor got re-acquainted with Sarah Goode, 21, a woman he’d known from the neighborhood where they both grew up.

The next morning, Goode was reported missing by her family. She’d never returned to their Medford home from the party. Goode was the youngest of nine children, and had a 4-year-old of her own.

It didn’t take long for police to link Taylor to Goode’s disappearance, rape and murder. Goode was attacked in the middle of the night of the party. According to a later coroner’s report, she was sexually assaulted and stabbed over 40 times; Her body was found naked from the waist down except for her shoes, and semen was recovered from the scene.

According to Newsday, the medical examiner’s office found a piece of metal lodged in her skull, but a murder weapon was never identified. She suffered “multiple sharp, force injuries about her head and torso,” Suffolk County Assistant D.A. Janet Albertson said at Taylor’s subsequent arraignment.

On July 29, 2016, Taylor received a life sentence in prison without the possibility of parole.

Endless Solitary

Two days prior to his suicide at Wende, Dante Taylor was evaluated by a physician who worked at Wende’s infirmary. Apparently Taylor had taken a common prison drug called K2, synthetic marijuana, while in his Keeplock cell. He was already serving an extremely long, 120-day Keeplock sentence for K2 usage.

Part of the reason for passage of the HALT act is to ban such long Keeplock sentences, according to Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, because the damage left on a person’s psyche is permanent. “These reforms are morally right, fiscally responsible, and will improve outcomes at jails and prisons,” she said.

Nevertheless, HALT was still years away from passage as Taylor struggled to maintain his sanity.

His reaction to K2 may have even caused a kind of psychotic break, since attending infirmary physicians diagnosed him with suicidal ideations and confusion in reaction to the drug, and eventually moved him into the Wende Residential Crisis Treatment Program, where they gave him Thorazine, an antipsychotic medication.

Unfortunately, a 2020 federal lawsuit by his mother and grandmother alleges, Wende medical authorities botched Taylor’s treatment, and threw him back into solitary the next day, even though conflicting diagnoses had noted his suicidal tendencies.

At 10:20 p.m. on Oct. 6, 2017, the first night back in his Keeplock cell from the infirmary, Taylor began having seizures due to usage of K2 for a second time.

The Beatings

When the seizures began, correctional officers were dispatched to Taylor’s cell.

According to the 2020 lawsuit, at least four of the prison guards beat Taylor’s “head, face and body with their batons, fists and feet.” The time at which this occurred, however, remains unknown due to lack of reporting from staff.

Still, the lawsuit reports that those in the surrounding cells heard Taylor “screaming in pain, the sound of sticks hitting his body and other sounds of an attack.” Taylor was beaten unconscious.

It was reported that the guards then “hogtied” Taylor while unconscious by “binding his hands and feet with zip ties, causing small lacerations to his wrists and ankle areas.” They then carried Taylor’s limp and motionless body by his biceps and ankles, face down to the floor and out of his cell to the top of a stairway that led down to the first floor and, the lawsuit alleges, threw Taylor down the stairs head first. Infirmary records show that as a result of the abuse, Taylor suffered multiple blunt force injuries to his head, neck, torso and extremities. His injuries were photographed in the infirmary at approximately 11:10 p.m., less than an hour after his seizures began and guards were on the scene.

Around 1 a.m. on Oct. 7, 2017, Taylor was transported to the Erie County Medical Center in Buffalo, where it was documented that he suffered “facial contusions, significant facial edema and ecchymosis, and complained of pain in his entire upper body including chest and back.”

Taylor was discharged from the hospital at approximately 4:30 a.m.

Although staff are not cleared to use excessive force, reports of its use were never publicly accessible until after the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, when New York legislators repealed 50-a, a section of the state civil rights statute that ambiguously protected law enforcement officers, whether NYPD or correctional officers, from their misconduct records being readily available to the public.

According to The New York Times, approximately 56% of more than 270 correction officers who faced disciplinary action between January 2019 and August 2020, “lied, misled investigators or filed incomplete or inaccurate reports.”

This act of violence against Taylor under the guise that he was non-compliant with staff orders will now show it is rooted in trauma and safeguarded by HALT Act due to his mental health issues.

Had Taylor’s psychotic break occurred in the wake of HALT’s passage, he would have been met by staff who would’ve had to have undergone 37 hours and 30 minutes of initial training prior to being assigned to work on a segregated confinement unit. Every subsequent year of such an assignment they would have to complete an additional 21 hours. Those specifically assigned to mental health units will take an additional eight hours of training, to be repeated annually.

No Correction in 'Correctional'

After his alleged beating, Taylor was returned to Wende from the hospital before dawn the next morning. Again, the suit alleges the on-duty medical staff “failed to order or conduct a mental health assessment of Mr. Taylor in the aftermath of his beating at the hands of staff,” according to the lawsuit, This failure explicitly violates DOCCS and the Office of Mental Health (OMH) policies that showed Taylor’s treatment was “Wholly inconsistent with good and accepted medical care and suicide prevention protocols.”

“Even if the on-duty medical defendants believed that Mr. Taylor had caused his own injuries through self-harm, those injuries — which were shocking in their severity — should have triggered an immediate assessment of Mr. Taylor’s capacity and intent to continue to engage in self-harm,” the lawsuit states.

The HALT Act would have ceased these actions if implemented before Taylor’s suffering, as the Act adds due process protections and prohibits someone being placed in segregated confinement before a disciplinary hearing and access to counsel has been had.

While multiple reports from New York state correctional officers, say that HALT created a false narrative to what solitary confinement actually is, and that its use is necessary to protect other staff and incarcerated people from dangerous people within the prison, Pate says it’s systematically abused, and a catch-all that makes prison officials and guards all powerful. “There is no representation, whatever the officer says is usually taken as gospel word that you did what he said he did, there is no opportunity for you to have someone witness on your behalf that what the officer says is not true. It's not necessarily [only] for violent people.” Records support Pate’s allegations, since 95% of people who faced disciplinary action are placed in solitary confinement, according to CAIC.

“You don't have to do anything specific to wind up in solitary confinement. You can be in solitary confinement for any miniscule thing only because the officers said you did,” Pate said, who suffered in solitary on Rikers Island for roughly two out of the 15 years he spent in the system.

Breaking a Broken System

The lawsuit that Darlene McDay, Taylor’s mother, and Taylor’s grandmother, Temple McDay, was filed a year before passage of HALT, in February 2020. It’s directed against the correctional officers who beat Taylor and against the officials and medical staff.

The lawsuit requests that the correctional officers and other administrative defendants from Wende are to be found guilty for acting in violation of, but not limited to, the Eighth and Fourteenth amendments of the U.S. Constitution. All in all, Taylor was denied his basic rights as a U.S. citizen, violating his Fourteenth amendment rights within one specific instance — they cannot abridge a citizen’s rights to a relationship with family members.

“The Constitution protects your right to have relationships with people of your choice within your family and that can't be intentionally interfered with,” said Katie Rosenfeld, Darlene and Temple McDay’s lawyer.

More germane with respect to HALT, under Eighth Amendment protections regarding confinement of someone in prison, it has been established that any prison guard who beats or infringes harm upon an inmate would constitute “cruel and unusual punishment,” violating the amendment.

Further, the lawsuit makes clear that both violations of the Constitution were even stipulated in the way Taylor was held. He was not allowed to contact his mother or any family member, and he was mentally tortured by this, because he was made aware of the restriction.

The Truth

Some of the reporting for this story could have been based on the Medical Review Board records released to McDay through a FOIA request. According to McDay and Rosenfeld, although heavily redacted, they confirm the falsity of the correction officers’ statements. Currently, the records are subject to a protective order, according to attorney Rosenfeld, and can only be shared with the parties in the case.

“I'm hoping at some point that can be lifted because frankly I think it's ridiculous that it's been marked that way, the information that is marked as confidential is largely about Dante's medical history, which is information that Darlene could disclose herself,” Rosenfeld said. “I think at a certain point we will want to challenge that designation and make the report more broadly available.”

Medical records and information shared in the lawsuit are otherwise heavily redacted from the reports McDay initially received, but Rosenfeld said they put it in the lawsuit because in their view, it isn’t confidential.

Two officers, according to the incident report from DOCCS, beat Taylor and later testified that they couldn’t recall exactly what they’d done.

Sergeant Timothy Lewaski, in a written statement, said upon his arrival to Taylor’s cell that he was striking his head, face and body on the cell floor and lockers, and would not listen to any verbal commands. Sgt. Lewaski went on to say Taylor was seen by medical staff and had self-inflicted injuries and “was assessed as being under the influence of K2.”

Yet the testimony of the officers was found by DOCCS’ own Medical Review Board to be “inaccurate,” noting that neither were “qualified to determine if an inmate’s behavior” and whether it was “drug related” or whether Taylor’s “injuries were self-inflicted.”

Rosenfeld, unfortunately says this is sadly normal procedure for the NY State Correctional System. “It's very common in correctional facilities for people to get assaulted and for the correctional staff to claim that injuries were self-inflicted,” Rosenfeld said. “I've had many cases over the years where correction officers claim that people hit their head against the wall and knock themselves unconscious. The problem is that the Department of Corrections doesn't scrutinize those ridiculous statements and allows them to submit these kinds of reports and doesn't go after them for it.”

The Office of Special Investigations (OSI) looked into the allegation made by other people in the Keeplock unit on the evening of Oct. 6, and the injuries Taylor sustained. It was found that Taylor was assaulted by numerous officers, and the injuries were inconsistent with staff reports of force compared to the reported assault.

The report from the OSI agreed with the allegations of Taylor’s assault which resulted in his injuries. Most importantly, OSI found that the “reports and statements of staff members involved being inconsistent or falsified.”

Rosenfeld explains that advocates have long been very critical of OSI because it doesn’t really investigate well and it doesn’t discipline officers, and it rarely makes finding that there’s been this conduct. In this case, she says, they did find misconduct in Taylor’s beating, which was “pretty unusual.”

***

DOCCS works behind closed doors, with transparency acting as a quality that is not at the forefront of their work.

“So how do you knock down those doors?,” McDay said. “I could say this whole thing of working with HALT has given me a little glimmer of hope that somebody is listening and that there is a possibility that somebody will care, and that there could be changes.”

“That's basically why I'm involved. That's why I continue to be involved. I'm hoping that it'll bring about change and I'll make changes in people's lives.”

McDay continues to defend those incarcerated, like her son’s friend who called her when he was first assaulted by the COs at Wende, who for safety reasons and his involvement in Taylor’s case, will go by the pseudonym Jackson.

“He's the one that called me when this happened to Dante, so if it wasn't for him, I wouldn't have known what happened,” McDay said. “He [Jackson] has nobody. He has no family at all. His mother died, his sister died. That's all he had.”

Because Jackson came forward, McDay has done her best to help him in return. In one instance, Jackson called McDay because he was in a cell with no running water and the officers told him to drink his urine. “[I was at work at the hospital during the first wave of COVID-19] and I was just so pissed off.” McDay recalled; she’s worked as a nurse practitioner for the past eight years. In response to what Jackson told her, she called the prison and advocated for him, threatening to write a formal complaint. It worked.

“He sent me a message a few minutes later saying ‘What the hell did you do? I never saw something happen so fast,’ and then all of a sudden I heard the water turn on because they turned off the freakin’ water.”

What HALT Cannot Repair

McDay is a grieving mother who suffered mistreatment herself by the Department of Corrections, and this part of the story is emblematic of bureaucracy turned into a form of cruelty.

After McDay initially learned that her son was beat up in prison, she called Wende. She explained who she was and that she needed to speak to whoever was in charge.

“Can I talk to the watch commander? Apparently something happened to my son and I need to know,’” McDay recalled. “I said ‘apparently he was brought the hospital’ and then he goes ‘no, he’s back.’”

At that moment, McDay believed that since he was not at the hospital then he must be okay and he wasn’t hurt as badly as she originally thought. They told her they would call her back, and after waiting some time she received no word. McDay called again for information, and the watch commander says he can’t share any information because “‘How do I know you are who you say you are?’” he said to McDay.

“All of a sudden, I finally got a phone call. It’s the chaplain and he tells me to sit down. I started screaming my f*cking head off. I just started screaming. I couldn’t believe it. I just remember standing here in my room, screaming my head off.”

After calming down, McDay’s next fear was telling her own mother, Temple McDay. “She has six children and I don’t even know how many grandchildren but Dante was her favorite.” Furthering the pain, Temple McDay had just lost her husband three weeks before.”

After she finally receives word of his death, McDay wants to get his body away from Wende as quickly as possible, but not a single staff member treats her with any decency after a slew of phone calls. One remark from the watch commander, and McDay felt her blood boil over.

“I started screaming my head off at him. I wanted to kill this guy.” After a few more attempts, she finally got Captain Meyer on the phone. She says he said he would try to get someone to call her back, with no care in the world.

“I said ‘Why don’t you pretend to have some compassion and humanity for one second?’ Nothing. Then I said, ‘I know who you are. You’re the person that denied my son was being harassed and now one of your officers has killed my son.’” The immediate reaction was denial, and after McDay asked: “Are you telling me that my son is not going to have any bruises on his face?” The lying was imminent.

“‘No, no. We all know that’s not true,’” McDay recalls Meyer saying over the phone, with a tone filled with undeniable carelessness.“Unbelievable. The things that they say and get away with are unbelievable. It’s just completely disgusting.”

Initially, Captain Meyer, who McDay had dealt with prior to Taylor’s death after she wrote a letter regarding Taylor’s harassment from another officer, came out to the visiting area to ask who Taylor’s mother was, but his first question? Paperwork.

“He’s just giving me a hard time about it like are you freaking kidding me? My son is dead. You piece of shit.” McDay said.

Over time, McDay has spent an upwards of $20,000 to defend her son. She refuses to let the Department of Corrections get away with this, no matter what she has to do. Her dedication to her advocacy and those currently incarcerated shines through her grief, as she fights for a just carceral system.

As people on the Senate floor said her son’s name, she believed that finally people had been listening.

“This shows that there's a possibility that there could be a change, that somebody does care and that they'll see the flaws in the system and maybe make it better for other people,” McDay said. “There's just so much that can happen for me at this point, but you know, maybe it makes it better for a lot of other people.”